INTERVIEW WITH BOTERO I

Title : LOCAL ROOTS, UNIVERSAL APPEAL

Author : Dr. Jolly Koh

As Published In : Star Mag

Date : Sunday, 12 December 2004

Fernando Botero, one of the most sought after Latin American artists today, was in Singapore last week for the opening of his first South-East Asian exhibition, When he stopped over briefly in Kuala Lumpur, he spoke with veteran local artist DR JOLLY KOH.

At first, my egalitarian nature made me feel uncomfortable about having to address Fernando Botero as maestro as everybody does. But after I spent an hour talking to him, I had no qualms in doing so.

The maestro’s conversation injected a breath of fresh air that has long been missing from local art discourse. The substance and depth of Botero’s thoughts were impressive. I found him knowledgeable, lucid and very articulate.

The nuances of Botero’s verbal expressions are difficult to capture with precision. And his inimitable Latin accent makes his talk all the more exotic. Furthermore, because some of his answers were abbreviated due to the context of our talk, I have chosen to comment on some of his views. My comments are in italicised parenthesis.

Thank you for giving us your time. I want to use this great opportunity to milk your artistic wisdom for our art world here.

Well, you know, the best artistic wisdom that I have can be seen in my exhibition in Singapore. There you will see something different, how I went my own way against the official line of art and against the fashion of the times. And, you know, it was difficult for a very long time, but I am glad I did that because now you can see a very different world.

(Here we see the young artist as a rebel, the artist asserting himself as independent and as an individual. But we shall also see the artist later as a traditionalist when he tells us how he spent years copying the old Masters. He once said, "Everybody at the academy - where he was studying - was trying to develop his own style, but all I wanted to learn was technique".)

How did you arrive at those sumptuous figures?

It started very early from my first watercolour in Colombia when I was painting figures in the market place – and somehow those figures came out voluminous.

Another major influence was when I went to Europe at an early age of 19 to study, especially when I was in Florence when I studied the art of Giotto, Massachio and all the other Italian Masters, I was fascinated by their sense of volume and monumentality.

I spent many years copying the Old Masters. Of course, in modern art everything is exaggerated – so my voluminous figures also because exaggerated.

(Here is an example of what happens when an artist has the opportunity to study masterpieces at first hand early in his career – an opportunity most young Malaysian artists do not have. Thus, the chance to see the works of a major 20th century artist such as Botero in Singapore should not be missed.)

There are some art writers here who believe that art should be socially relevant and should even affect social change. What is your view on this?

There are two positions, you know. First of all, especially in the 1930s, there were these Marxist artists who believed that their works could change the world. Of course, they were naïve you know, because art does not have that kind of power, that is, the power to change social or political values.

But art as a testimony of its time is justified. We think of Goya and Picasso. But, you know, Picasso’s Guernica did nothing because Franco still continued for 25 or 30 years after Guernnica and the painting did not change the political situation. But as a historical document people will remember that bombardment.

(Guenica is a Spanish town in which more than 1,000 people were killed when it was bombed in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War; rebel general, Francisco Franco, successfully fought the Republican government and installed a fascist government that ruled Spain for almost 40 years.)

Now I tell you this: I have also painted the atrocities in my country and I gave 50 of these paintings to the national museum of my country. But, of course, I have never said that these paintings will end the violence or crime in Cololmbia.

But these paintings are testimonies of the times. For people who do not read history, paintings have an immediacy that other media do not have. So there are two positions-art that will change society, or art as historical testimony.

(Obviously, not all art is historical testimony in this sense. Most of Picasso and Goya’s works are not political testimonies. In fact, most paintings are not political; one has only to think of Degas, Cézanne and Bonnard – and so the list can go on and on. And neither are most of Botero’s paintings and sculptures political.)

In your paintings I see a very strong sense of design or, what some might say, abstract qualities, and they are very beautiful. Is this consciously arrived at or does it come unconsciously?

Well, I’ll tell you. A painting is a decoration and I am very conscious of the design and the decoration of the painting. It is a balance between the decorative elements and the expression and drama. From the first moment one has the flat surface to decorate, and that comes close to abstraction.

So your views of decorating the surface, and beauty, contradict the present ethos, which repudiates all of that?

Well, that’s right…but what can I say? For thousands of years decoration has been a big part of painting. The malaise all began with that man Duchamp, you know, A recent survey that came out in the papers said that Duchamp was the most influential artist of the 20th century. (French artist Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a 1917 porcelain urinal, was voted last century’s most important artwork by 500 British art experts on Dec2.)

(Here we both giggled with amusement.) What’s happened to Picasso and Matisse? You know, time is the great leveller. So many famous artists of the 19th century are now forgotten. Time will place all these things in perspective.

One of the problems is indifference. People get tired and bored – so the art world has to present something different to attract the crowd, to shock and to even offend in order to attract attention.

What advice do you have for young (and not so young) artists in Malaysia?

I believe strongly that for art to be honest and effective, it has to have its roots in the land and place. All great art has its roots.

So Malaysian artists should draw from its place – from Oriental art and whatever is local to the place. And through the four elements – of colour, composition drawing and poetic expression – and through the beauty of colours and its poetry, the work becomes universal.

The trouble with so many young artists today is that they copy from the latest art fashion found in the art magazines and they become international. But universal art is something different. In my case I draw from the tradition of folk art in my country and use those four elements that I referred to just now, and through that I transcend the locality and make my art universal.

You may start with something local but you must be faithful to the art of painting. You know, for example, Van Gogh, when he painted he sky in Provence, he did not just stick to the local, in the end he was faithful to painting. You must have those four elements to give your work quality, and with that quality your art becomes universal.

❚ Dr. Jolly Koh (who has a doctorate in education) is a leading senior artist in Malaysia. His recent book, ‘Artistic Imperatives’, of selected paintings and writings (published by Maya Press) is available at leading bookstores.

A Walk in the Hills.

of his views. My comments are in italicised parenthesis.

Thank you for giving us your time. I want to use this great opportunity to milk your artistic wisdom for our art world here.

Well, you know, the best artistic wisdom that I have can be seen in my exhibition in Singapore. There you will see something different, how I went my own way against the official line of art and against the fashion of the times. And, you know, it was difficult for a very long time, but I am glad I did that because now you can see a very different world.

(Here we see the young artist as a rebel, the artist asserting himself as independent and as an individual. But we shall also see the artist later as a traditionalist when he tells us how he spent years copying the old Masters. He once said, "Everybody at the academy - where he was studying - was trying to develop his own style, but all I wanted to learn was technique".)

How did you arrive at those sumptuous figures?

It started very early from my first watercolour in Colombia when I was painting figures in the market place – and somehow those figures came out voluminous.

Another major influence was when I went to Europe at an early age of 19 to study, especially when I was in Florence when I studied the art of Giotto, Massachio and all the other Italian Masters, I was fascinated by their sense of volume and monumentality.

I spent many years copying the Old Masters. Of course, in modern art everything is exaggerated – so my voluminous figures also because exaggerated.

(Here is an example of what happens when an artist has the opportunity to study masterpieces at first hand early in his career – an opportunity most young Malaysian artists do not have. Thus, the chance to see the works of a major 20th century artist such as Botero in Singapore should not be missed.)

Horse, an example of Botero's gangantum sculptures.

Botero likes things big - subjects, canvases and ideas. In the background is Virgin with Child.

There are some art writers here who believe that art should be socially relevant and should even affect social change. What is your view on this?

There are two positions, you know. First of all, especially in the 1930s, there were these Marxist artists who believed that their works could change the world. Of course, they were naïve you know, because art does not have that kind of power, that is, the power to change social or political values.

But art as a testimony of its time is justified. We think of Goya and Picasso. But, you know, Picasso’s Guernica did nothing because Franco still continued for 25 or 30 years after Guernnica and the painting did not change the political situation. But as a historical document people will remember that bombardment.

(Guenica is a Spanish town in which more than 1,000 people were killed when it was bombed in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War; rebel general, Francisco Franco, successfully fought the Republican government and installed a fascist government that ruled Spain for almost 40 years.)

Now I tell you this: I have also painted the atrocities in my country and I gave 50 of these paintings to the national museum of my country. But, of course, I have never said that these paintings will end the violence or crime in Cololmbia.

But these paintings are testimonies of the times. For people who do not read history, paintings have an immediacy that other media do not have. So there are two positions-art that will change society, or art as historical testimony.

(Obviously, not all art is historical testimony in this sense. Most of Picasso and

Goya’s works are not political testimonies. In fact, most paintings are not political; one has only to think of Degas, Cézanne and Bonnard – and so the list can go on and on. And neither are most of Botero’s paintings and sculptures political.)

In your paintings I see a very strong sense of design or, what some might say, abstract qualities, and they are very beautiful. Is this consciously arrived at or does it come unconsciously?

Well, I’ll tell you. A painting is a decoration and I am very conscious of the design and

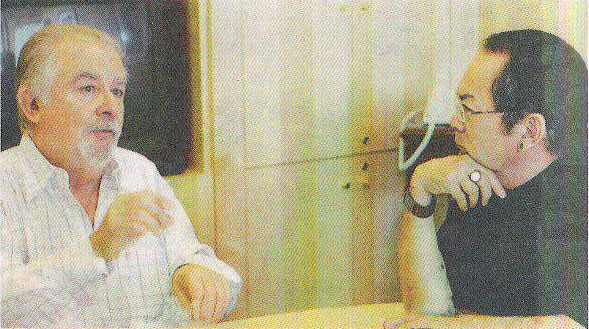

The maestro and Koh deep in discussion. - Photo by AZLINA ABDULLAH

the decoration of the painting. It is a balance between the decorative elements and the expression and drama. From the first moment one has the flat surface to decorate, and that comes close to abstraction.

So your views of decorating the surface, and beauty, contradict the present ethos, which repudiates all of that?

Well, that’s right…but what can I say? For thousands of years decoration has been a big part of painting. The malaise all began with that man Duchamp, you know, A recent survey that came out in the papers said that Duchamp was the most influential artist of the 20th century. (French artist Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a 1917 porcelain urinal, was voted last century’s most important artwork by 500 British art experts on Dec2.)

(Here we both giggled with amusement.) What’s happened to Picasso and Matisse? You know, time is the great leveller. So many famous artists of the 19th century are now forgotten. Time will place all these things in perspective.

One of the problems is indifference. People get tired and bored – so the art world has to present something different to attract the crowd, to shock and to even offend in order to attract attention.

What advice do you have for young (and not so young) artists in Malaysia?

I believe strongly that for art to be honest and effective, it has to have its roots in the land and place. All great art has its roots.

So Malaysian artists should draw from its place – from Oriental art and whatever is local to the place. And through the four elements – of colour, composition drawing and poetic expression – and through the beauty of colours and its poetry, the work becomes universal.

The trouble with so many young artists today is that they copy from the latest art fashion found in the art magazines and they become international. But universal art is something different. In my case I draw from the tradition of folk art in my country and use those four elements that I referred to just now, and through that I transcend the locality and make my art universal.

You may start with something local but you must be faithful to the art of painting. You know, for example, Van Gogh, when he painted he sky in Provence, he did not just stick to the local, in the end he was faithful to painting. You must have those four elements to give your work quality, and with that quality your art becomes universal.

❚ Dr. Jolly Koh (who has a doctorate in education) is a leading senior artist in Malaysia. His recent book, ‘Artistic Imperatives’, of selected paintings and writings (published by Maya Press) is available at leading bookstores.

INTERVIEW WITH BOTERO II

Title : THE BEGINNING...

Author : Dr. Jolly Koh

As Published In : Star Mag

Date : Sunday, 12 December 2004

Back when the artist was a non – conformist rebel, he was once forced to sell his work for as little as US$20 – a world away from the US$1mil price tag slapped on one of is works two months ago by auction house Christie’s in New York. The maestro talks about his early years with DR JOLLY KOH.

WHEN was your first major breakthrough?

The major breakthrough came in the mid ‘60s when a museum director from Dusseldorf in Germany invited me to exhibit in five museums. After that, many galleries in Europe approached me.

But for the preceding 20 years it was difficult. It was difficult for me to get a gallery in New York to show my work because at that time Abstract Expressionism was all the rage. Many of my friends from Colombia went to New York and became Abstract Expressionists and sold their works successfully. You know, I was like a leper at that time.

How did you manage?

I really counted my pennies in those days. I was selling my works for so little – for between US 100 and US 200 when Colombian friends my age were selling theirs for US 1,000. Some people even offered me US 20 for a painting. I had to sell many paintings for almost nothing to survive but I still managed to make a living through my art without having to do anything else. (Here he spoke with much nostalgia and a touch of pain.)

So your friends were successful then?

Yes, they were very successful.

And now?

I don’t know – they were successful for only a short time and now they have disappeared.

(Betero made those remarks with some amusement. What the above phenomenon points to is that artists are individuals and individuals survive. Artistic movement do not survive – they come and they go. Thus artists who only follow artistic fashions will perish with those fashions. Only artists who remain individuals will survive the rise and fall of the various artist fashions. I believe this is a profound artistic truth not realized by many people.)

THE ART OF BEING JOLLY

Author : Veronica Shunmugam

As Published In : The Edge, Options Section

Date : Monday, 2 October 2006

It is never an easy conversation with modern artist-academician Dr Jolly Koh, for whom having good ideas is of no use without coherent expression. Yet, it is rare to find a painter whose wit has been so sharpened by a collective four decades of having lived in the UK, US and Australia. VERONICA SHUNMUGAM relishes the chance to get him going on his new exhibition Jolly Koh, which is currently on show at Art Salon, and other fascinating aspects of Malaysian art.

Veronica: Congratulations on your new show, Jolly. Are all the works new?

Dr Jolly Koh: All except for one, Blue Moon, which I painted in 1978.

Besides the sculptures Isomorphic Form I and II, which works have a new element?

It’s hard for one to be objective about one’s work. Having said that, what I think are relatively new are Malaysian Landscapes I and II. I rarely work on a horizontal format and birds. The other reason these are new is because I’ve named them Malaysian Landscapes, which I did with a touch of irony and protest. These works come closest to being my “political paintings”.

Why?

Because most (local) paintings of Malaysian landscapes are of kampung scenes.

…which you did paintings of a long time ago.

Yeah, in 1955 (Purple Shadows) and 1957 (Red House). But there is nothing kampung about Malaysian Landscapes. So, I am saying to Malaysian society that if it wants to progress, it must transcend its local self and go global in the economic, sociopolitical and artistic realms.

And can I needle you with a point you made – in earlier media interviews and in your interview of famous painter-sculptor Fernando Botero – that artists shouldn’t try to change the world?

I am not trying to change the world at all. One’s artwork is an expression. So, I’ve painted Malaysian Landscapes as an expression of my values and ethos. So, it is not in any way contradictory to my views.

Well, you also did say that if at all an artist wanted to portray social change on the canvas, then he should do it through very good technique and training.

Yeah. Art is an expression of the values of the artists but it is also an expression of beauty.

What do you have to say then to young artists who hold demonstrations, or do very jarring works of art to try and bring about social change?

They are basically protesters. In a way, they are no different from Umno Youth staging a protest at an international conference. If you or anybody else wishes to call those protesters artists, then by the same token, you should call other protesters artists and isn’t that stretching the term “artist” somewhat?

The other point about young art – which I’ve got no problems calling art – is that you must realize that these are different art forms. I am concerned with the art form of painting.

Those other guys that do video or installation (art) have got nothing to do with painting. If you like, you can call them all artists but doing this just blurs the distinction. It is part of one’s mental development to be able to distinguish between film and paintings as art forms. Artists who do video art – even if these works have been shown at an art gallery – should be compared to filmmakers or theatre practitioners, not painters such as myself.

Maybe the art gallery in question was trying to open the doors to a wider variety of artists?

That’s okay. But then, why not host a theatre performance or a film festival in the following months? I think this would be most unfortunate and confusing, especially for – may I say – people who are uncritical.

But some people would say that artists – such as one who recently used the medium of video for an exhibition at an art gallery – are meant to blur boundaries and break down lines that make up categories of race, religion or art?

Well, what boundaries has the artist in question blurred that other artists in the US hadn’t already blurred in the 1970s?

When you first moved back to Malaysia (from Australia under the Malaysia My Second Home programme) about two years ago, you bemoaned how young artists hardly approached a senior artist like yourself to have conversations about art. Has the situation improved since?

No. The whole environment is not conducive to that kind of thing. What I have done and am still doing is conducting my monthly painting class at the National Art Gallery. That’s the kind of approach and dialogue I have taken. There is one young artist by the name of Ng Siew Keat who is taking my class.

Which young painters here make your grade?

By the nature of the thing, don’t expect too many good artists at any one time. In the days of Rembrandt or Van Gogh, there were hundreds of thousands of artists, but how many Rembrandts were there?

Is it especially difficult for young painters in Malaysia to develop?

My oblique answer is that a lot of young painters in this country, sad to say, decline very badly. There are a lot of bad paintings here.

What are the reasons for this?

In the last 30 years, the state of art school and paintings – not just in Malaysia – has been very bad. One of the reasons for this is that art schools don’t teach painting as a discipline anymore. So, art students go into this discovery of multimedia or filmmaking when what they should be doing is attending film school. It’s all “do your own thing” or “everything is art”.

Title : Commitment to Art

As Published In : Malaysia Property News

Date : Thursday, May 15, 2008

Commitment to Art

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Property developer Lai Voon Hon has always prided himself on his sense of aesthetics especially when it comes to art, architecture and contemporary design.

As a former architect who practised in Hong Kong, the president and chief executive officer of Ireka Development Management Sdn Bhd is concerned that the various condominium developments undertaken by his companies must project and deliver a certain standard of quality and finesse.

In projecting the upmarket image of his latest development Seni Mont’ Kiara, Lai has allocated space for a permanent art gallery aimed at supporting the Malaysian art scene.

This luxury condominium project, comprising 605 units set on 3.57 hectares (8.83 acres) is undertaken by Aseana Properties Ltd (19.6% owned by Ireka Corp Bhd) together with OCBC via Amatir Resources Sdn Bhd.

A guest at the launch shows Jolly Koh (centre) and Lai Voon Hon (right), one of the works featured in the book.

At the recent launch of the art book Jolly Koh at the Seni Art Gallery, Lai remarked that his companies have always strived to infuse each project with a sense of life enriching element, which he called “soul”.

“For Ireka and Aseana Properties, supporting art development and increasing aesthetic awareness have always been our corporate commitments.

"This is especially significant as the art infra-structure in Malaysia today is still lacking,” explained Lai.

“In keeping with our commitment to ensure fine arts become part of Seni’s heart and soul, we have commissioned and purchased exceptional art pieces from well-known Malaysian artists and sculptors.

"One such artist is Jolly Koh.

“It gives us great honour to support the first coffee-table book on the art of Jolly Koh which documents his achievements as one of Malaysia’s finest artists.”

The 272-page hard-cover book features significant paintings and major works done by Koh from 1955 to 2008.

Most of the 210 selected drawings and paintings were sourced from private collections and institutions in Malaysia and abroad.

Namely, the Singapore Art Museum; National Art Gallery, Malaysia; National Art Gallery, Victoria, Australia; Bank Negara Malaysia; Galeri Petronas, Malaysia and the J.D. Rockefeller III Collection in New York, among others.